Pursuit of Recurring Revenue & Three Views of the CloudPursuit of Recurring Revenue & Three Views of the Cloud

What constitutes monthly recurring revenue -- and how the quest for it is influencing Cisco, Avaya, NEC, and Mitel

January 2, 2019

For most No Jitter readers, the cloud represents an opportunity to change telephony business models coupled with the challenge to deliver or consume communications solutions that correspond to the cost and reliability of existing on-premises solutions. When we discuss cloud and UCaaS, we’re usually looking at it through user and vendor views.

In the financial world view, however, cloud represents monthly recurring revenue, or MRR (sometimes called annual recurring revenue, or ARR). MRR has become the new holy grail for technology companies in the enterprise communications space. As Timothy Chao, author of “Seven Clear Models of Cloud Computing,” stated, “Cloud is not a technology, it is a business model.” The stock value for many technology companies has become directly tied to their delivery of a sustainable MRR business model.

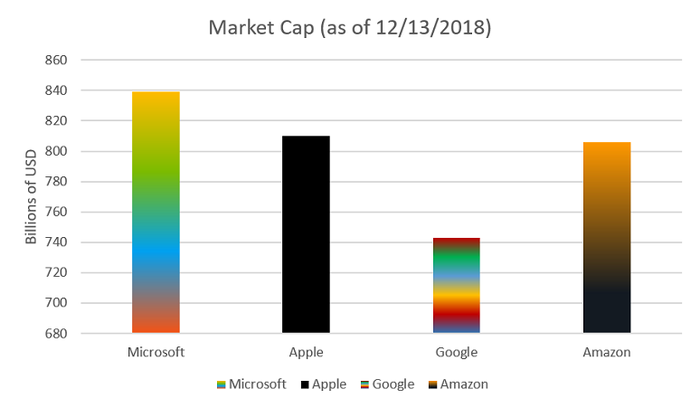

On Nov. 30, 2018, Microsoft’s market cap topped Apple’s, making Microsoft the most valuable publicly traded company in the world.

Numerous Wall Street publications have largely attributed Microsoft’s significant rise in market capitalization to its cloud computing solutions, including Azure cloud services and Office 365.

Many experts believe that Microsoft has significant upside remaining because Microsoft’s growing cloud business generates lots of MRR. Google and Amazon, two other companies that generate substantial MRR through cloud services, also have tremendous market capitalizations.

The financial market’s MRR focus is having a significant impact on the communications market, where nearly all vendor and service provider companies are strategizing on how they can increase their own monthly recurring revenue, and hence, their own valuations. In the balance of this article, we’ll discuss three MRR perspectives accompanied by our analysis of how we believe Cisco, Avaya, Mitel, and NEC -- the market leaders in terms of telephony installed base -- should each execute to achieve their best valuations.

Continued on next page: Cisco + BroadSoft Examined Through an MRR Lens

Cisco + BroadSoft Examined Through an MRR Lens

Much has been said and written about Cisco’s acquisition of BroadSoft, which closed in early 2018. At the recent BroadSoft Connections event, Cisco provided some clarity on the combined companies’ roadmap and product and service offerings. However, we think there must be some additional serious debates going on within Cisco about increasing the MRR from the Webex group.

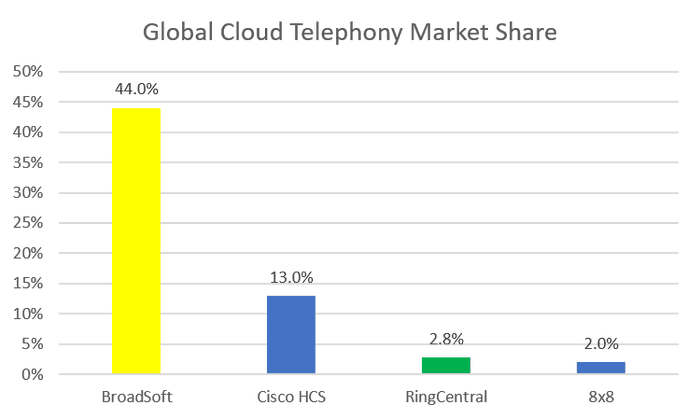

Consider that BroadSoft’s BroadWorks software, which is usually installed and run by service providers, has approximately 44% share in the cloud-based telephony market. BroadWorks isn’t sold under a SaaS model but rather a typical perpetual software licensing model in which BroadSoft makes telephony and UC software that it sells to service providers. These service providers then offer BroadWorks-based UCaaS services from their own clouds. The MRR goes to these service providers.

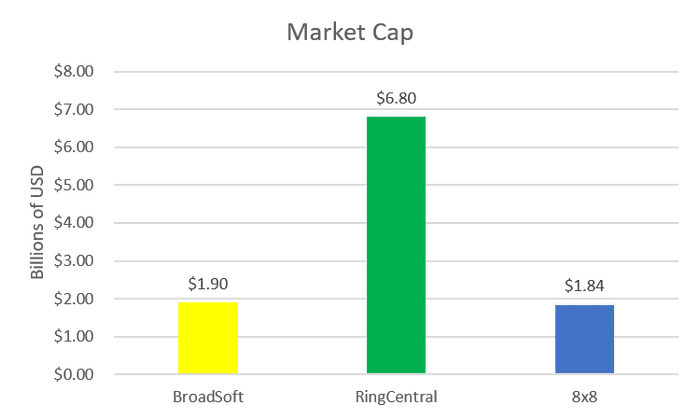

Now consider the tremendous valuations given to cloud-based telephony providers. RingCentral, with about 2.8% of the cloud telephony market, has an astounding market cap of $6.8 billon. Similarly, 8x8, with about 2.0% of the cloud telephony market, has a market cap of $1.8 billion.

These market valuations create tremendous incentive for Cisco to host BroadWorks itself and offer it as a service, as opposed to selling it as software under perpetual licensing. If we were to simply average the valuations of RingCentral and 8x8 on a market share basis, and apply this valuation to BroadSoft, it would make BroadSoft running under a true SaaS business model worth about $70 billion. With the 13% market share held by Cisco Hosted Collaboration Service (HCS), it is not hard to imagine a scenario in which Cisco hosts all its HCS-based and BroadWorks-based telephony services. In such a scenario, this hosted UCaaS services business would be worth about $100 billion. Add this to Cisco’s existing $212.7 billion market cap, and Cisco’s worth tops $300 billion -- that’s not a figure shareholders and executives can ignore. Furthermore, given the current market valuations for MRR streams, as many of the approximately 100 million on-premises end users -- as reported by Cisco -- move to cloud, the company’s market cap would skyrocket if Cisco hosted the telephony services itself.

Although Cisco has said it will continue to offer BroadWorks to its service provider customers, we believe the financial drivers are so strong that Cisco will, over the next four to five years, take this business and convert it primarily to a cloud-based services offering within its Webex division. Cisco has two nascent MRR/SaaS telephony offerings: BroadCloud, which is a Cisco-hosted version of BroadWorks that service providers can private label; and Webex Calling, which is a Cisco-branded hosted solution also based on BroadWorks (see related post, “The Market Impact of Cisco’s BroadSoft Acquisition”).

We predict that in the mid-2019 timeframe Cisco will begin promoting these MRR-generating SaaS offerings with all the marketing muscle the company possesses. To make either successful in the enterprise space, Cisco will need to enable something like Microsoft’s Direct Routing, which allows a company to use its existing PSTN trunking service or a service provider to offer SIP trunks.

Continued on next page: What About Avaya, NEC, and Mitel?

What About Avaya, NEC, and Mitel?

MRR is the driver that we believe should and will influence what Avaya, Mitel, and NEC begin offering for their large deployment customers. These three companies are the other large installed base telephony players.

In its recent financial analyst session, Avaya claimed it has 145 million installed base seats. Mitel claims about 70 million seats, including the large installed bases it acquired over the years from Aastra, ShoreTel, and others. Based on market share data over time, NEC should be somewhere in the range of 120 million seats. And, don’t forget Cisco’s approximately 100 million seats. Combined, these companies represent 435 million installed base endpoints!

The opportunity for each of these vendors is to provide a compelling cloud transition offer that can become the path of choice for their installed bases. This is how the financial markets are viewing these companies. For example, in initiating coverage of the new Avaya stock in December 2018 with a Neutral rating, Goldman Sachs said, “While we are encouraged by the stabilization and early evidence of top-line improvement, we remain on the sidelines until we get more comfortable with the growth trajectory and see evidence of an acceleration in customers’ cloud migration” (emphasis is ours).

If Avaya really has 145 million active endpoints, then with the right cloud business model offers, some percentage of those would see logical value in retaining their Avaya solutions but under an MRR business model. For example, Avaya did a deal with Bosch in 2017 for a five-year managed service “cloud” offer that works out to between $6 and $8 per month per seat. If Avaya can transition 20% to 30% of its existing base, this represents 29 million to 43 million cloud seats. At an average revenue of $8 per month, a 30% transition generates an annual recurring revenue stream of $4.2 billion. Cisco, Mitel, and NEC are sitting on similar multibillion-dollar annual recurring revenue opportunities. For each company, the opportunity is huge. For Mitel, a transition of 30% of the installed base would be 21 million seats.

The emerging challenge in cloud is increasingly going to be one in which the incumbents transition their existing installed bases to their own clouds versus the rip and replace required to move to a competitor’s cloud. If Avaya, Mitel, and NEC can transition 40% or 50% of their existing installed bases to their cloud solutions, the annual recurring revenue for each would be larger than the current annual sales from their on-premises businesses. History will be an interesting judge of the ability of the incumbents to transition their installed bases.

In recent vendor mass migrations, first to Cisco with VoIP and then to Microsoft for collaboration, the companies’ adjacencies outside telephony drove their market moves. Cisco leveraged its data network adjacency to win in VoIP transitions and Microsoft leveraged the Office software with its collaboration and UC functionality to drive personal productivity. In each case, the adjacency led to about 60% capture of the transitions (based on analyst market reports and data). From this we can assume that the maximum churn during this type of transition is 60%.

However, the transition to cloud is complicated because all the premises-based vendors still have significant numbers of both TDM and pre-SIP IP phones in their installed bases that customers will have to replace in a cloud migration. This will reduce competitive advantage for these legacy vendors among these customers. Mitel, however, should have an easier transition since it is sixth globally in cloud telephony subscriptions, according to Synergy Research, and it provides CloudLink, which enables any of its existing telephony platforms to work with the new functionality in its cloud service.

Continued on next page: Should a Managed Service Generating MRR Qualify as Cloud?

Should a Managed Service Generating MRR Qualify as Cloud?

One significant point that is often overlooked in the cloud/MRR discussion is that most of the traditional large enterprise telephony solutions are single instance. This includes offers from Avaya, Cisco, Mitel, and NEC. Most analysts and industry pundits (and multitenant UCaaS vendors) argue these aren’t cloud, even if they’re deployed in an MRR business model.

In a single-instance model, dedicated software “instances” are deployed for each customer organization, which generally makes offering dedicated-instance cloud solutions cost-prohibitive for small-scale installations. In the SMB UCaaS delivery model, a multitenant system is critical to delivering a competitively priced cloud solution. However, while this pedantic view of cloud as requiring multitenancy is valid for smaller organization deployments, for larger organizations, the cost of a dedicated single-instance decreases with scale and eventually becomes irrelevant.

For example, a typical Avaya Aura or Cisco Call Manger solution has a minimum of four to six servers or virtual machines (VMs) for a redundant, highly available deployment, and may have dedicated gateway hardware as well. This number grows as additional services and capabilities are added. In a single-instance solution, servers, networking, and other resources are dedicated to the single customer, regardless of scale.

In our experience, the five-year cost for the dedicated infrastructure (servers, networking, data center, support, etc.) is around $50,000, which when amortized over five years has an annual cost of approximately $10,000 per year for the UCaaS provider to offer this type of solution. If this was deployed for a five-person company, the cost to the provider for each user would be $167 monthly just to cover the costs of the “core” deployment. In a multitenant model, the five users share the core with tens of thousands of other users from other organizations, so the cost per user of the core is a small fraction.

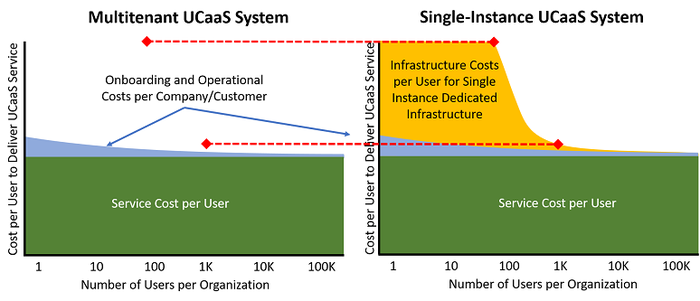

The figure below compares a UCaaS provider’s per-user cost and the organizational cost for the multitenant and dedicated single-instance models. The chart shows the three cost components of service delivery (typically called cost of sales in finance terms).

Per-User Costs: The green is the cost of providing the service to the individual user. This includes all the real-time processing, the individual services (telephony, conferencing, collaboration, etc.), bandwidth, PSTN access costs, most technical support, and anything else that scales linearly with the number of users. Generally, this is 90% to 95% of the cost of service delivery, as it reflects most of the real operational costs over the life of the solutions. This includes all the infrastructure resources required to support the individual user.

Per-Company/Customer Costs: The blue area represents costs associated with the company/customer. These include onboarding, billing, company level support, etc. Typically, the costs of supporting an organization are relatively small.

Single-Instance Infrastructure: The orange block on the Single-Instance chart (at right) shows the amortized cost per end user for the dedicated equipment required for a single-instance deployment. Compared to a multitenant solution that may support 100,000 users, a dedicated instance for 500 users on the same level infrastructure will have a large unused capacity. This is reflected in the higher-per-user costs when the number of users per organization is small.

If the cloud services are essentially the same, the only real cost difference between multitenant and single-instance deployment is the cost of the dedicated infrastructure required for the latter. As can be seen, per-user and per-company costs for each cloud seat are the same except for the infrastructure required for a single-instance deployment.

On the multitenant systems on the left, you can see how this impacts the delivery costs of a multitenant base offer. As company size grows, the actual decrease is minimal given the relatively low per-company costs. The right chart shows the same analysis for a single instance. As you can see, for deployments with fewer than 100 seats, the cost impact of the dedicated equipment makes a single-instance uncompetitive. This can be seen from the red line at the top showing comparative costs at 100 seats. However, at about 1,000 seats (the red line in the middle), the added cost of the dedicated infrastructure for single instance is now allocated over a larger population and the added cost becomes insignificant.

Understanding this cost structure illustrates why virtually all the Cisco HCS providers have a 400-seat minimum for an HCS deployment to the cloud. However, as you move to 1,000 seats and above, the added allocated cost per user of the single-instance deployment drops dramatically. By this point, the $10,000-per-year dedicated core costs, when applied to 10,000 users, becomes only eight cents per month. It essentially becomes irrelevant in the overall UCaaS cost to deliver a seat. So, a single-instance deployment becomes very competitive at 1,000 seats and above. At the point the capacity of a unit of softswitch computing is equal to the size of a single company UCaaS deployment, there is no difference at all.

Continued on next page: Conclusion

Another cost-effective way to provide a single-tenant solution is to have smaller individual software deployment footprints. This would facilitate deployment of a large number simultaneously using a large number of VMs. Interestingly, for Avaya IP Office or other smaller key system-derived offers, deploying the relatively small software footprint of the core softswitch for each customer into a multi-VM-per-processor structure enables single instances to be cost-effective for sub-100 seat customers. (By the way, this is why many VARs use a company like Asterisk to deliver small cloud solutions.)

In our opinion, whether a UCaaS deployment is multitenant or single instance, the fact that it’s purchased on an MRR basis and is operated by the third party makes it a cloud solution. Whether the contract includes discounts or requires a time commitment doesn’t change the cloud MRR delivery model.

This begs a question: Is a deployment where everything is the same except where the software is deployed a cloud solution or not? Should the location of the processing determine cloud versus non-cloud, MRR versus non-MRR? In the old days, a managed PBX was a complete stand-alone system. Today, deploying a cloud UCaaS solution in the customer’s data center means deploying just a few VMs (and a real-time capable infrastructure). In some cases, there are no physical resources to manage since the customer data center does that for the vendor and just provides VMs to deploy into. In many ways, this is akin to deploying software in the Amazon Web Services cloud.

From the customer perspective, a service in which the communications solution runs on premises but is managed by a third party is still an OPEX monthly cost and is perceived exactly the same as if it were a cloud solution. The only difference is where the software runs. By enabling the software to run on the customer premises, generally in a private-cloud deployment, two major advantages accrue. First, the security concerns of data being in the cloud are dramatically alleviated; even though it is a billed under a cloud/MRR business model, the core servers, software, and data stay on the customer premises. Second, in a deployment where the core software runs on the customer premises, the customer pays for all the infrastructure required in the data center (compute, storage, network access, etc.), making it less expensive for the managed services provider.

The conclusion appears obvious. Larger customers from Cisco, Avaya, Mitel, and NEC will move to the MRR cost models typically seen in “the cloud,” but they will generally move to dedicated single-instance deployments, running either in their own private clouds or in private clouds hosted by service providers. For both the financial industry evaluating the performance of the companies in this sector and the end customers, multitenant, single-instance, and varied/hybrid deployment locations all have the same impact: They transition from the capital-intensive periodic purchase with its accompanying operational expenses to an MRR-based, OPEX-oriented, managed services model.

For enterprise customers, the financials and the implementation specifics will be resolved via market competition and the pricing impact it will have. For many Cisco UCM, Avaya CM/Aura, Mitel MiVoice on-premises, and NEC on-premises customers, their sheer size will minimize the cost penalties of the single-instance deployment. For smaller companies, however, these solutions won’t scale down to the SMB and smaller mid-market levels, so Cisco, Mitel, and NEC have developed or purchased their own multitenant offers and Avaya has indicated it will have one soon.

Conclusions

We believe the three views of what constitutes a viable cloud solution: customer, vendor, and financial may converge to a common view that cloud is more appropriately defined as an MRR business relationship where the customer never “owns” the software. Focusing on MRR/subscription relationships as the defining factor of cloud enables a true evaluation of the offers and market success. With this viewpoint, we can draw a few key conclusions.

We believe that the financial markets will consider MRR in multiple forms as viable cloud business models. This may/should include all the MRR models emerging in the market:

Multitenant cloud

Managed services regardless of who owns the equipment and where it’s operated

Subscription services (like Cisco Flex Plan), even if the organization runs the solution itself

We believe that in the mid-term, Cisco, Avaya, Mitel, and NEC will try to migrate many of their larger customers over to an MRR model in which these vendors themselves manage the dedicated- instance solution, regardless of whether it runs in the vendor’s cloud, in a private on-premises cloud, or in a third-party data center. Their valuations depend on migrating a sizeable portion of their bases to this model and the financial markets see this as attaining “cloud” evaluations.

The overall UCaaS market will migrate to this more general view of MRR being the valuation driver rather than cloud multitenant technology being the valuation driver.

As the concepts of cloud and MRR in the UCaaS space mature, the movement to cloud will drive acceptance of the different deployment models. Large organizations with security and operational concerns can move to a cloud-based model that incudes local or dedicated cloud deployments but reflects the operational and MRR values of cloud. Smaller organizations will tend toward the large multitenant clouds that can deliver lower cost with small numbers of users. This broader definition of cloud will accelerate the adoption of cloud by enabling optimized “cloud” solutions for a range of customer requirements.

The result of enabling large enterprises to migrate to MRR/cloud easily, even with the security of having the software running in their own private clouds, will be dramatic. If the current large enterprise telephony premises incumbents can migrate a substantial portion of their installed bases to the new range of cloud/MRR models, the financial outlooks could be very interesting.

About the Author

You May Also Like